Plinko and I go way back… all the way to October of 2017.

In my data science class, there was a question about a simple finite Plinko game. Plinko, of course, is the completely skill-based game from The Price is Right where a player lets go of a disc and watches it bounce between pegs. Players can then win prizes depending on its final location.

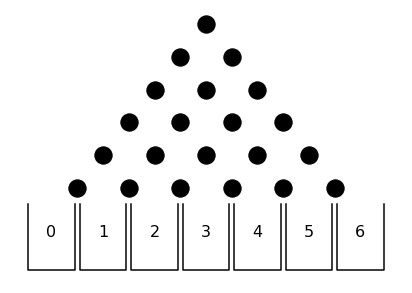

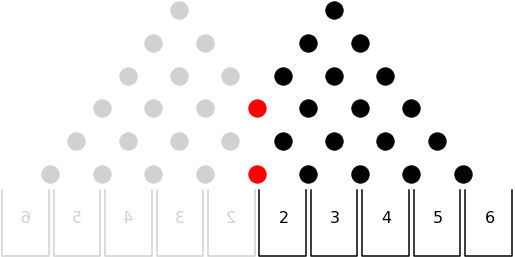

Here’s the basic image from the homework:

It can look a little weird at first but this pyramid of circles provides an easy way to investigate some exciting aspects of mathematics. Each of the black circles represents a peg. When the disc hits the peg, it can either move to the left or the right. In this example, we assume that there is an equal chance of the disc moving in either direction. Though it is possible to solve this problem with a different probability using different methods, it is far easier when probability of a rightward move is .5. The buckets at the bottom represent possible end locations. While in the show you can win cash prizes, here you only win personal satisfaction. One thing that you can start to see is that the number of times that the puck moves to the right corresponds to the number of its end bucket.

Try it out for yourself! If you follow down from the top peg to any bucket, the number of right moves corresponds to the final bucket where it lands. So if a path is RLRLRL, it ends up in bucket 3 as there were 3 right moves. This also holds true no matter the order of the moves. RRRLLL, LLLRRR, and LRLRLRLR all end up in bucket 3.

We can even validate this with a simulation:

def plinko_trial(num_rows=6, p=0.5):

bucket = 0

for ii in range(num_rows):

bucket += np.random.choice([0,1], p=[1-p, p])

return bucket

def easy_plinko(num_samples=int(1e2), rows=6, p=0.5):

final_bins = [plinko_trial(rows, p) for _ in range(num_samples)]

return final_bins

def graph(final_bins):

fig, ax = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=1, figsize=(12,6))

ax.hist(final_bins, bins=[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7], normed=True)

graph(easy_plinko(10000))

Now this looks exactly like the distribution for a binomial random variable. This makes sense, too. Each time the disc reaches a peg can be thought of as an individual trial. For each trial, there is the probability that the disc moves to the right. The final location is the sum of successful moves to the right. Now this sounds exactly like a Binomial random variable. Every successful trial represents a move to the right. Every failure is a move to the left. The number of trials is simply the number of peg rows that the disc encounters. Therefore, the given image can be represented as samples from the random variable:

From here, the problem only gets more interesting. Solving for a single pyramid is fun and all but it lacks something that the actual Plinko board has: boundaries.

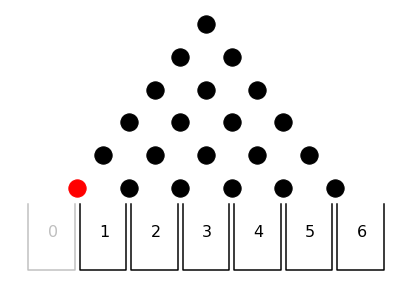

Boundaries provide the exciting (and confusing) part of the problem. The idea of a boundary can be seen below:

Here, the board has walls at one side which is represented by the red dot. You can think of the boundary being at the ‘.5’ mark. When the wall only separates off a single bucket, it is easy to see what happens. Every disc that was going to land in bucket 0 ends up in bucket 1. Now this is the important thing to recognize about a disc’s interaction with a wall: The end location of a blocked disc is the reflection of the original destination about the bounding wall.

Before we start to unpack that claim, let’s take a detour to talk about another game: pool.

In pool, whenever you are trying to line up a shot that rebounds off a wall you use the Law of Reflection. This law states that the angle of reflection is equal to the angle of incidence. Therefore, you can line up your shot by imagining that there is another pool table on the other side of the wall.

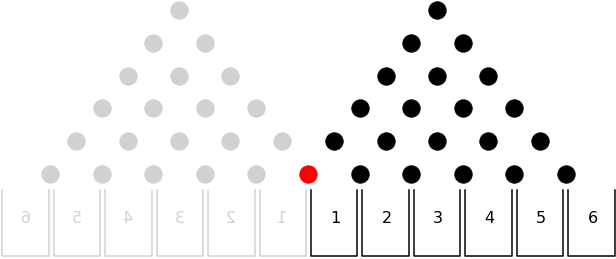

With this in mind you can imagine that instead of the disc being rebounded by the wall, it simply continues onto another Plinko board mirrored on the other side. In this mirrored Plinko world, all directions are switched. So a left in our world becomes a right in this one.

Since it is impossible for the puck to ever end up in bucket 0, you can think of it as ending in another bucket 1. This is the simplest possible example and it only gets more exciting from here.

The idea of a mirrored Plinko world becomes far more useful when multiple buckets are cut off by a boundary. While only one path is impacted in this instance, it is possible that there could be multiple buckets cut off on a side. Here is an example with two buckets cut off by a wall at the ‘1.5’ mark:

Applying the same idea of a mirror board, we can see where the disc will end.

Remember, I previously claimed that the end location of a blocked disc is the reflection of the original destination about the bounding wall. By applying the idea of a mirror board, we can easily see how this is the case. You can even try and prove it to yourself by following along various paths just like we did earlier. Every path that would have ended in bucket 0 ends in bucket 3. Every path that would have ended in bucket 1 ends in bucket 2. This is a very cool and useful trick but it does have its limitations. It only works when it is equally likely that the disc travels in either direction. The moment that the probability of a move to the right is no longer .5, this mirror trick no longer works.

Using this information, we can start to solve for the actual board that is used on The Price is Right.

There’s a problem here that we have yet to discuss. This board isn’t an easy to use triangle. It’s a rectangle with many different start locations. Luckily for us, we’ve spent way too much time thinking about this game and have a solution. Each of the top pegs can be thought of as a separate basic Plinko problem. What makes them different is the boundary applied to each one.

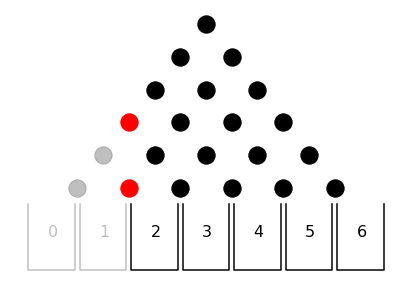

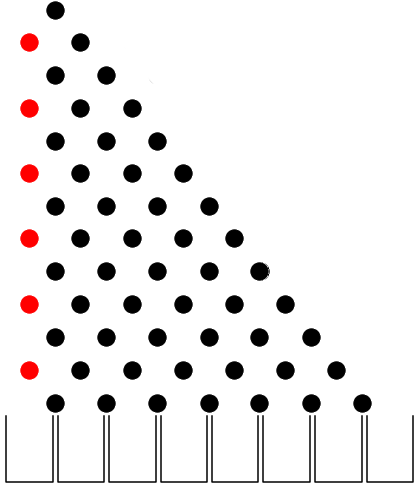

After way too much time, I managed to create an image representing the smaller Plinko problem that begins at the left-most peg:

I’d mock this up for the other problems but it would take far too long. It also wouldn’t be as useful as one would think.

This strategy presents a problem where you must translate the individual Plinko’s buckets to the real ones. The true board has different buckets than any individual problem. You can see this while trying to determine what the left-most bucket should be labeled. In the eyes of the subproblem, it is bucket 6. However, in the eyes of the overall problem, it is bucket 0. For the subproblem that begins on the next peg to the right, that same left-most bucket could be considered either bucket 5 or bucket 0.

Managing this difference becomes increasingly difficult to both manipulate and describe. Luckly, there is a better way of solving these problems. Instead of treating this complex problem as the sum of the realizations from 8 bounded random variables, we can instead think of it as a single markov chain.

That’s where it really gets exciting.